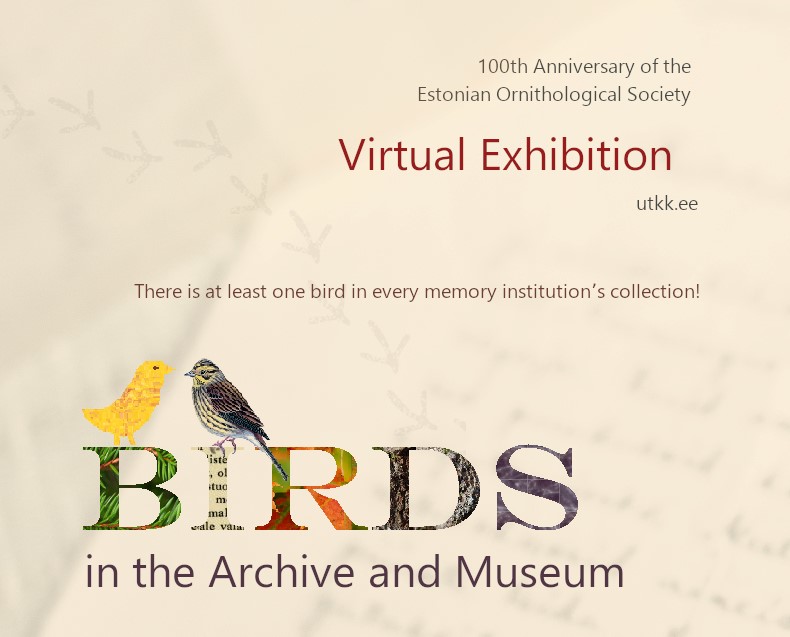

Birds in the Archive and Museum

In 2021, as part of the 100th anniversary of the Estonian Ornithological Society (Birdlife Estonia), we began to compile a reflection on how birds have flown from the natural environment into the collections of memory and research institutions. To do this, we asked libraries, archives and museums to send us birds and their stories that have been considered important to be preserved. The curators were rather excited to see whether they would manage to get hold of at least 100 exhibits – and the answer was yes! However, if someone feels that any collection is still unrepresented or would like to send in additional birds – these will be gratefully received (keskkond@utkk.ee).

The exhibition is supported by a virtual tour on the museum page of the Literature Center – all garden birds should be found there too!

Read more