Birds and the war

Blog post by Elle-Mari Talivee, project Envirocitizen. May 2022

On this year’s Walpurgis Night I participated for the first time in a citizen science project of counting the Eurasian woodcocks in Estonia – the bird of the year here. The count is rather easy: the males fly over clearings at dusk with a peculiar sound, performing a courtship flight known as ‘roding’, and one just needs to count the flights over a fixed period. My mom’s house in the countryside stands on a little meadow in the woods and the sounds of the woodcocks are something that have always been part of the spring evenings there while making a bonfire. I managed to record 15 woodcock flights that night before they left the sky to the witches.

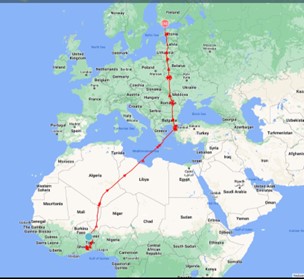

A couple of days before, I had noticed that another but very rare wader (quite similar in appearance to the woodcock) had returned to Estonia. On April 26th, the great snipe called Tuljak (named after delicious chocolate sweets, not the famous folk dance) arrived back home in Estonia after wintering in Ghana. The bird is carrying a GPS-tracker, so his route (7000 km in 20 days) could be followed on the map. Mr Tuljak made some stops on his long journey, a longer one in Turkey and some shorter breaks in Romania, Ukraine and Lithuania. From the interactive map of the Estonian Eagle Club one can follow the routes of other migratory birds with trackers – black storks, common cranes, various eagles – returning North. The great snipes often travel at night and inevitably I wondered what Tuljak thought of the fires of the war, of Russia bombing Ukraine.

Those birds were lucky to pass unharmed. The genocide Russia is trying to carry out in Ukraine (today I already hope it has totally failed) has brought along ecocide and a loss of biodiversity as well. The forests already began to burn in 2014, when Russia started the war in Donbas. The wildlife of the Meotyda National Nature Park, founded in 2009 also for rare waterbirds by the Sea of Azov close to Mariupol has suffered long from fighting in the area. In this March the battles close to Kherson caused fires in the Black Sea Biosphere Reserve with unique habitats for birds in one the largest biosphere reserves in Ukraine. These are but a few examples.

A war journalist has written about the birds close to the front in the middle of Europe in May 2022:

“As we draw closer to the front, we meander around potholed roads. Dima tells me there’s intense fighting at the moment. We get stuck behind two pheasants waddling in front of us. “They’re totally deaf,” he says. “Shelling has blown out their eardrums. We can hoot all day and they’ll never hear.””

His experience reminded me of several examples from a book by the Scottish ornithologist Hugh Gladstone, Birds and the War (1919) about WWI. Gladstone collected text samples and news about birds in the war, some of them deafened by air-raids and air-craft bombs, dead linnets with their eardrums split, but also about species which got used to the cannon fire and used the abnormal quantity of insects while nesting on no-man’s land or in old shell-cases. Or found a new place to nest: ‘Swallows flew around the heaps of ruins that represented their former homes, and it was some days before they became reassured and built in the military huts constructed against the battered walls’ (p 116–117).

These observations from letters and diaries are like a tragic mode of citizen science. The book quotes a Scottish miner shortly before his death on the Western front: “If it weren’t for the birds, what a hell it would be! I watch them singing, and something comes to into my throat that makes me almost greet [‘cry’]” (p 134).

War Twitter has shared the story of the evacuation of the lions of the Kharkiv Ecopark and the tapirs from the Feldman Ecopark Zoo. The brave Ukrainians have also thought about their favourite birds, the white storks returning from Africa, arriving to war, and starting to build nests on bombed-out roofs: I have noticed suggestions to construct platforms for these nests, help them with installing artificial nests. The birds seem to carry hope.

The Bank of Estonia, Eesti Pank is going to issue a two-euro coin for Ukraine designed by a student refugee Darja Titova from the war. The designer has depicted a girl as a symbol of tenderness, protecting a little bird in her hand. Even in the war.